humanitarian Legacies: Dr. Harvey Cushing & Dr. Louise Eisenhardt

By Taruni Tangirala

A special thanks to Terry Dagradi, Director of Yale’s Cushing Center

Dr. Harvey Cushing, often dubbed the father of neurosurgery, seamlessly melded together the trifecta of practice, research, and teaching with the assistance of his collaborator, Louise Eisenhardt. His academic pedigree begins with earning his bachelor's degree at Yale University in 1891, completing his MD from Harvard Medical School in 1895, and undergoing surgical training at Johns Hopkins University. Having worked with hundreds of patients yearly as the surgeon-in-chief at Peter Brent Brigham Hospital (now Brigham and Women’s Hospital), his meticulous documentation of each patient and surgery never seemed to have faltered.

With the evolution of photography, imaging technologies, and education technologies, there is no limit to what we can accomplish in studying human pathology. What, then, is there to learn from a physician-scientist whose heyday was around a century ago?

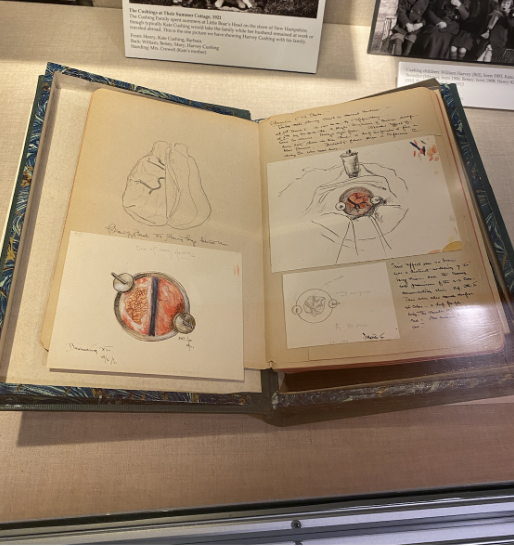

Throughout his life, Cushing was an avid reader and consumer of knowledge. His expansive rare book collection lies right above the Cushing patient specimen exhibit at Yale, and he has been the author of multiple books on neurosurgery, neuropathology, and patient care. His punctilious nature, whether it be a simple anatomical sketch, his research in neuropathology, taking patient histories, or even creating a framework for monitoring basic biometrics during surgery which has since been followed for years to come, was one of his most defining characteristics as a physician. His observational skills heavily underscored his aptitude for anatomical sketches– as mentioned by Terry Dagradi, Cushing could come out of surgery and recall every anatomical attribute in concise detail, as reflected in his sketches. Consequently, his work provides further justification for the medical humanities. In research and practice, physicians must be able to observe beyond what they are trained to see at school, which requires a creative temperament to facilitate education in the sciences.

Figure 1. Anatomical Sketches by Cushing

Even more than research practices or insights into neuropathology, the rigor with which he treated every patient is one of the most salient learnings for clinicians and researchers from Cushing’s life. There is a beautiful meticulousness to each of his patient histories, wherein he recorded every facet of a patient’s disorder in a manner almost unknown to his time. From anatomical photographs to basic biometrics, Cushing utilized every piece of technology available to him to create (what was then) a comprehensive outlook on neuropathology. His keen observation skills that facilitated his research were also crucial to his clinical practice; as opposed to the modern-day caricature of the physician with fingers glued to a keyboard and eyes glued to a screen, Cushing’s patient-oriented skilled observational nature may have also been an effect of the times he lived in. Broadly speaking, while the modern-day day physician is (to an extent) burdened with bureaucratic obligations on their computer, Cushing’s era of physician-practitioners would have seen the patient as their primary recipient of attention.

Figure 2. Patient Records by Cushing

Does this mean that today’s physicians are inferior to Cushing? No– the augmentation of medical knowledge and technologies is, simply put, a double-edged sword. Cushing’s work, however, serves as a potent reminder to let the focus of clinical practice be the patient and not just the science.

Accordingly, one of his most remarkable contributions to neuropathology was his detailed account of specimens collected from diseased patients, eventually known as the Cushing Brain Tumor Registry. What started as a personal collection of pathological specimens became an extensive, formal registry accounting for specimens, photographs, and records from over 2,000 case studies of patients, almost reminiscent of today’s large-scale biomedical datasets.

Figure 3. Anatomical specimens of the Cushing Brain Tumor Registry

Today, Terry Dagradi of the Yale Medical Historical Library directs and curates the exhibit. From her own experience, while there have been broader concerns regarding the ethicality of collecting these specimens from those not directly affiliated with the patients, she has had several conversations with descendants of the patients from whom these specimens have been collected. All of these interactions have been pleasant and involved interest in and gratitude for the collection from the relatives. One such anecdote was that of a man facing a brain tumor who had heard of a great-aunt who had a similar condition; having contacted Terry and found records on his aunt, he seemed to feel gratification when learning about his family history. Dagradi also expressed that there is much evidence of Cushing being well-loved by his patients.

Cushing may not have finished all this work without the rigor that Cushing’s right-hand woman and collaborator, Dr. Louise Eisenhardt, contributed. Eventually becoming an expert in tumor diagnosis in her own right, she was a trusted colleague of Cushing’s who, when he joined the WW1 war effort, finished a manuscript of his on neurological tumors. Her dedication allowed for the completion of the tumor registry and countless other projects led by Cushing.

Figure 4. Louise Eisenhardt’s Contributions

Perhaps the contributions of Dr. Eisenhardt and Dr. Cushing were largely thanks to practicing in a time that served as a turning point for human civilization. Nonetheless, the patient-facing directive used by Cushing and Eisenhardt in both research and clinical practice is a compelling reminder not to forget the core of why we practice science– for the sake of humanity.

Most information presented in this blog post was adapted from the Yale Cushing Center Exhibit.